Love Without Words

A story about passion, longing, love, and grief

Two years ago, an NYT article about Anderson Cooper and his podcast "All There Is with Anderson Cooper" (Season One) introduced me to the concept of "anticipatory grief".

Two years later, I have a profound new understanding of grief, grief brought on by losing a parent, grief that, no matter how much anticipation, I can never be ready for.

My mother passed away from heart failure two months ago today. Every single day, I am reliving the memories of Mom, and learning to live with my grief. Writing this essay is the beginning of the healing, if grief is ever to be healed.

This is for you, Mom, and the time we had together.

(If you are reading from the emailed newsletter, to listen to music embedded throughout this essay while reading, you may want to read from the Website or Substack App. The music was from Mom’s 1979 concert recording. See footnote for details.)1

♪ ♪ ♪

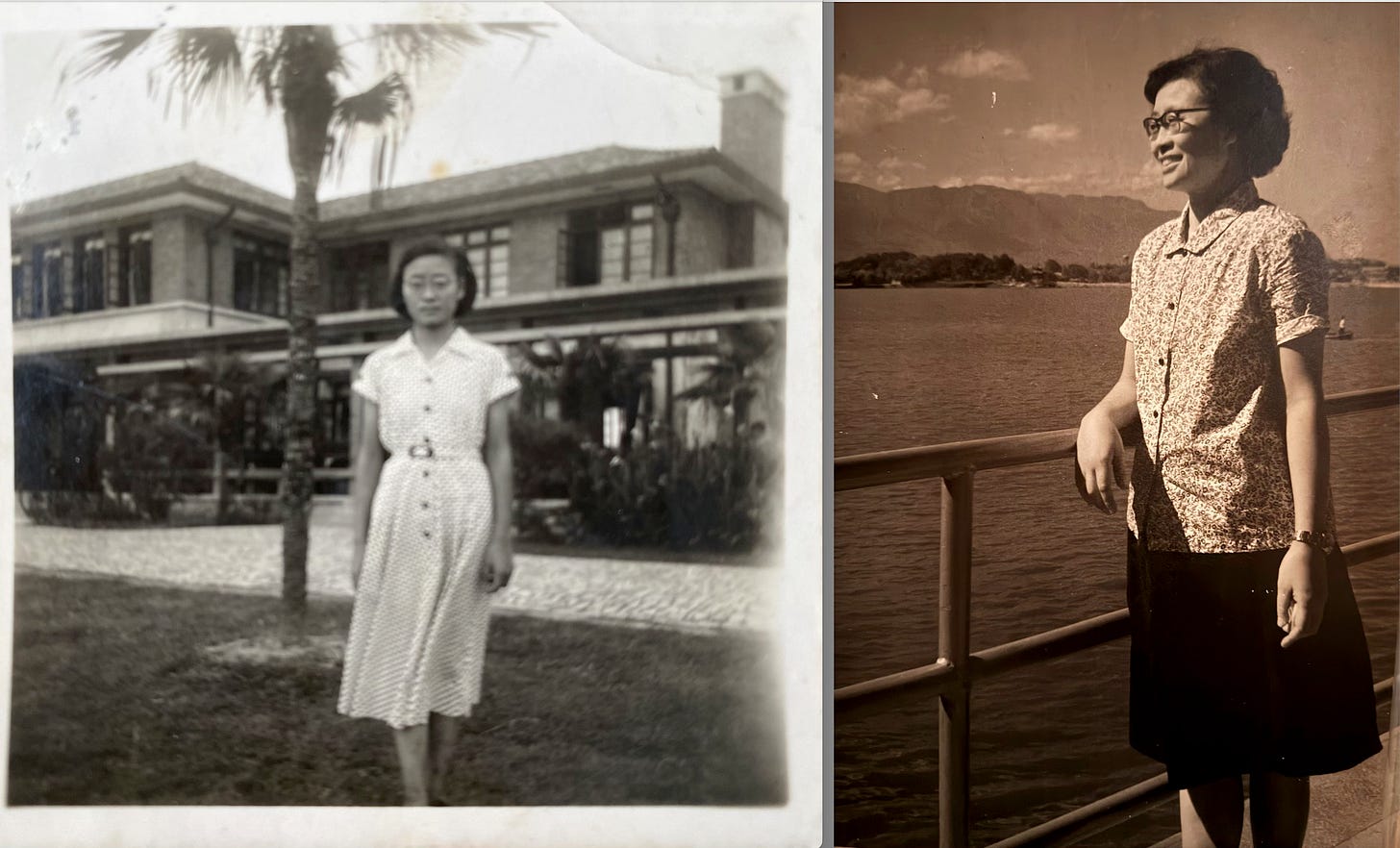

Mom grew up in a modest family in pre-WWII Shanghai. Her parents came from drastically different socioeconomic backgrounds with only one thing in common: their Christian beliefs. Mom attended Sunday School at an early age, and it was there that the hymnal singing accompanied by an old organ led her to music. One day, she climbed onto the organ bench, her foot barely touching the pedals, she played the hymns she had heard—and that was the start of her music journey.

Mom didn’t have access to a real piano until she was 13 when a local piano dealer lent an upright piano to her father as a form of interest payment for a personal loan. The moment she put her hands on the keys, piano became her life-long companion.

At school, she was often lost in class, partly because she was the youngest in her class, and partly because the teachers— who came to Shanghai from various provinces to escape the Japanese invasion—all spoke various dialects. To that shy and quiet girl, the piano was a friend she could talk to without using words, and music was a world she could escape to, a world of love and dreams.

That world was shattered when Mom turned 17. Her father was pronounced “anti-revolutionary” by the new government, and sentenced to 15 years in jail. The family of eight lost their only income overnight.

“I remember feeling fearful and ashamed at the same time when I made trips taking Grandma’s jewelry and coats to the pawn shop,” Mom used to tell me. “Until all there was left was a pile of pawn tickets.”

Mom, who was the oldest of six siblings, became the main provider for the family by giving piano lessons to children of well-off families in their homes. Too often she was not able to collect the payment for that day’s lesson. She’d wandered the dark and cold streets of Shanghai, too afraid to return home to her mother’s expecting gaze—that payment was what Grandma needed to put dinner on the table. To my 17-year-old Mom, piano had become something more than a passion, it became what she could depend on to provide a livelihood for her family.

What also shattered, were Mom’s hopes and dreams of becoming a concert pianist—with an “anti-revolutionary” father, she was deemed not worthy of such opportunities after she entered the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. And yet music transformed into a more intense love in Mom’s life where she could pour all her unspoken passion and unfulfilled longing. She swallowed her pride and ambition, and went on to teach at the Conservatory after graduating at 21.

♪ ♪ ♪

I was born in 1965, five years after Mom married my dad (her first and only boyfriend), a law school student who turned into a middle school teacher because nongovernment members practicing law was not permitted. That was one year before my grandpa was released from prison, and one year before the start of the Cultural Revolution.

Mom’s world of music was disrupted once again. The “Red Guards of the Revolution”—young students of the “red” families, from Dad’s school—stormed our home and took possession of anything they deemed to have Western or traditional influences, including Mom’s music scores and her vinyl records. The irony was that around the same time, the families of these Red Guards started to move into the garden houses in our neighborhood once known as the French Concession. Suddenly, people of all trades and backgrounds became unlikely neighbors.

Our Mozart, an old upright piano built by the Canadians in the early 20th century, miraculously escaped the ill fate of being destroyed and remained in the corner of our living room, untouched.

One hot and humid summer night, the air was stale in the house, and all the windows and doors were popped open. I perched on the windowsill, restless because of the heat. Dad was grading papers. Mom sat at the piano. Tentatively, she started the opening Recitative of Chopin’s G minor Ballade. This was one of Chopin’s four ballads said to be influenced by the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz’s narrative poem about a Lithuanian hero, Konrad Wallenrod, who fought against his people’s enemies and died a tragic death. Chopin’s ballad is as dramatic as Mickiewicz’s poem and finishes with a triumphant closing depicting the hero’s laugh in the face of death. Despite not having played the music for several years, Mom was immersed in the deep emotion of the music, and delivered a splendid rendition. There was a silence after the ending chords. Then, from the darkness of the stifling summer night, a loud applause erupted outside the house—neighbors had gathered in our garden unbeknownst to us.

For a brief moment, that applause induced a shock inside our room, and that shock soon turned into triumph—Mom had communicated a complicated and powerful emotional story through her music, to people she could never have imagined being able to communicate with, using words.

And for a brief moment, the world seemed alive again. Until silence returned.

Dad was diagnosed with acute leukemia in 1976, towards the end of the Cultural Revolution. He succumbed to the disease two years later, leaving Mom, a 44-year-old widow, and two young daughters ages 13 and 10. Mom had once again become the sole provider for her family.

She started giving private piano lessons to supplement her salary from the conservatory, which was barely enough to feed and clothe the three of us.

Every Sunday morning, I would awaken to the sound of her teaching in the room next to our shared bedroom. The lessons would go past dinner time and several days a week, Mom would go directly from the teaching stool at home to the piano bench at the Conservatory’s concert hall, accompanying her college students, the first college class after the end of the Cultural Revolution, for evening recitals. In those days when commercial activities were not allowed outside of state-run institutions, instead of monetary payments, her students paid for private lessons with commodities of all kinds, from newly harvested rice to fish rationed from companies the parents worked for to offering to fix our 601 reel-to-reel tape player. During holidays, painted tin cans of cookies and mooncakes, and bamboo baskets of fresh fruits would pile up high on our dining table. Once in a while, a well-off student family would offer an entire leg of Jin-Hua ham (think of it as a Chinese version of Jamón), as their gift and gratitude for Mom’s teaching.

Despite being a single mother living in a time when most daily necessities were rationed, Mom had made sure my sister and I never lacked anything to live a comfortable life.

♪ ♪ ♪

There was one thing lacking in our daily life: the phrase “I love you.” Emotional communication was not deemed a necessary skill for most Chinese. They believed words were not the warren of love. A roof over heads, food on the table, and a decent education were enough love most parents could give, and physical discipline was often a way to show love for your children. Although my mom never subscribed to the discipline part of the theory, she practiced the Chinese tradition of avoiding verbal communication of any intimate nature—a trait I wish I had not inherited.

The only spanking I received from her was related to piano practice. I don’t remember the exact act of my rebellion, but a memory of the bright, red velvet slipper embroidered with tiny plastic beads she used to whip my behind is still vivid in my mind. Years later, when I brought up the story, she contested that the physical punishment was out of her unwavering love for me.

“I just wished you could one day love music the way I did,” she defended herself.

“But you never really talked to me about why I had to play piano.” I protested.

“Well, not everything needs to be explained,” her voice a bit sheepish. “I knew you’d appreciate it when you grow up.”

She was right. I did not inherit her musical career, but I am forever thankful that the appreciation of music she instilled in me has become the Eden of my soul.

Mom has always been drawn to everything sentimental: classic Chinese poetry, 19th-century European literature, early 20th-century Hollywood romantic movies, and of course, music. Yet she is awkwardly clumsy with words. I have no memory of her uttering the three magical words of “I love you”. I wonder if Mom has ever been told that she was loved. Is that why she never utters these three words herself?

But there was plenty of love in my upbringing; love you could feel and love you could see.

On Sunday mornings, my sister and I would crawl under Mom’s cotton duvet and plead for stories. From Scheherazade and Sinbad in One Thousand and One Nights to Monkey King and Piggy Monk in Journey to the West, and from Snow White to “Little Cabbage” Xiao Bai Cai (Chinese Cinderella without the fairy godmother and Prince Charming), my mom would recite these stories from memory. She’d embellish the stories—from books she read when she was a girl—with vivid details from her imagination. The stories came alive in the minds of two little girls, and I began my journey into the literary world well before I could read. When Western and traditional Chinese literature books were banned, I had Mom’s stories to fill the void.

“Genie waved his hand in the air and voilà! There in his giant hand is a frying pan, three fat sausages lying in the middle, sizzling!” Eyes widened and mouth-watering, pan-fried sausages became my favorite breakfast item. And as soon as I learned to read and books were available, reading became my obsession.

There was another Sunday ritual, ear wax picking. Yes, gentle ear-picking that tickled and soothed at the same time. We would sit by the French windows on small stools, face to face, my head on Mom’s knees with one side facing upward. Bathed in the warmth of the sun, I sighed with contentment and giggled until I drooled.

To me, that is “I love you.” We didn’t utter the three magical words, not back then, not ever. But there are never any doubts in my mind that I have been loved.

I say “I love you” often to my son, husband, and friends, in English. But for reasons I have yet to fully understand, I don’t say “I love you” to my mom or my sister. I never uttered these words in Chinese. Is this because of how I was brought up, in a society and culture that avoids intimacy? Is it some sort of “emotional deficiency” that makes me run away when things get uncomfortable? When I no longer have the chance to say these words to the people I love dearly, is that going to be the source of grief?

♪ ♪ ♪

I can’t help but wonder, did Mom have the “I love you” moments from me?

Mom loved taking me out for lunch on her paydays when I was little. It was at the table of “The Red House”—a restaurant at the corner of the street across from our home with French and Russian roots —that I learned how to use a fork and knife properly and spoon soup away from me. The mother-daughter pair often drew looks of amusement from fellow diners. We talked about these moments years later, and I know she cherished them just as much as I do. Was that love we remembered?

When strawberries were in season, Mom would show me how to immerse the bright red berries in silky white milk. If budget allowed, we’d upgrade milk to ice cream—a true luxury! Those were the most fragrant strawberries we both agreed we ever tasted. Was it love that we were tasting?

For the last 8 years of her life, Mom lived in the Bay Area. I’d take her to restaurants whenever I visited her. Walking a few blocks had become a real effort for her, so she often waved for me to walk ahead. I always wanted to translate the menu for her, and she’d promptly protest: “I can read English!” But when the server approached, I’d promptly take over, ordering what I thought was best for her. Did she consider moments like that an “I love you” from me, her always-in-charge and impatient daughter?

Between my visits, I would call Mom weekly. Every so often, I’d get agitated and raise my voice, because, for the Nth time, she mixed up her medication dosages after we’d discussed the doctor's instructions. She’d refuse to use what I wrote down for her and vehemently disagreed that we had the dosage discussion. Would she consider my insistence and annoyance my way of expressing “I love you” to her?

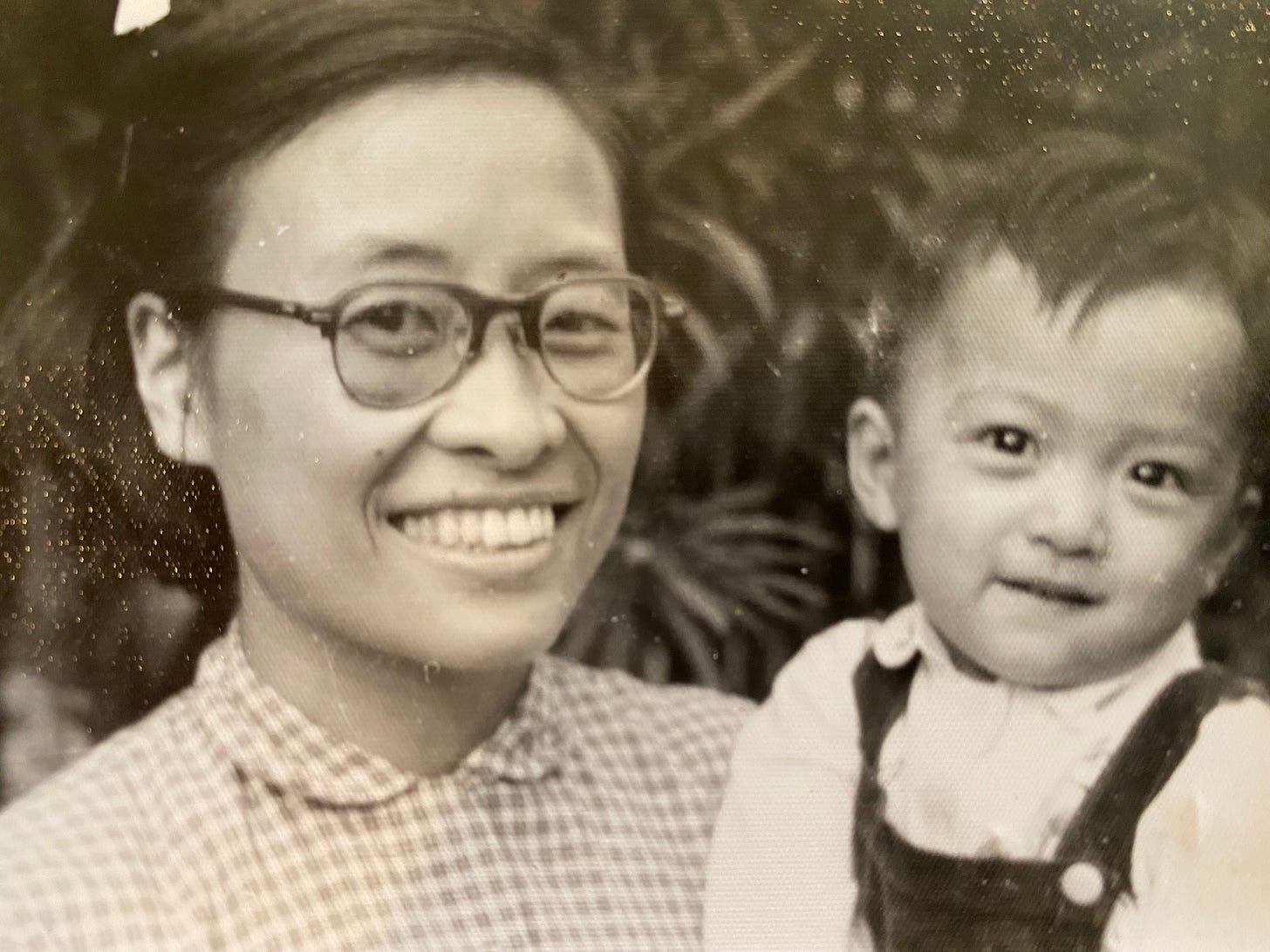

When I gave birth to my son, Mom volunteered to take the night shift so I could get some shut-eye. In the wee hours of the night, there would be a gentle knock on my door. “Hello, Mommy! Time for milk!” She cooed softly while handing me the baby. 40 minutes later, I’d hand him to Mom and sink back into my pillow. Mom quietly closed the door, baby fast asleep in her arms. Are these moments of love for her?

Now my son is 6’1” and a hard metal and punk music lover. When he gave me a CD set of Mendelssohn’s piano solo work “Song without Words” as a birthday gift, I was pleasantly surprised.

“What made you pick that?” I asked. He simply said, “I heard Grandma playing these growing up and it always brings me comfort listening to them.”

That was the best gift I have ever received from my son, knowing that my mom’s love for music and her family, has passed down.

♪ ♪ ♪

My dear Mom bid her farewell to the love of her life—music and family—last month. Her health had been declining in the months leading to that morning when her heart let go of this life on earth. It was expected and yet an event I was not and never will be ready for.

I sit on the floor with the artifacts of Mom’s life scattered around, her 9-decade-long life encapsulated in these boxes and envelopes. Late summer sun's last rays casting a golden hue in the room, and there is no sense of loss, but her presence.

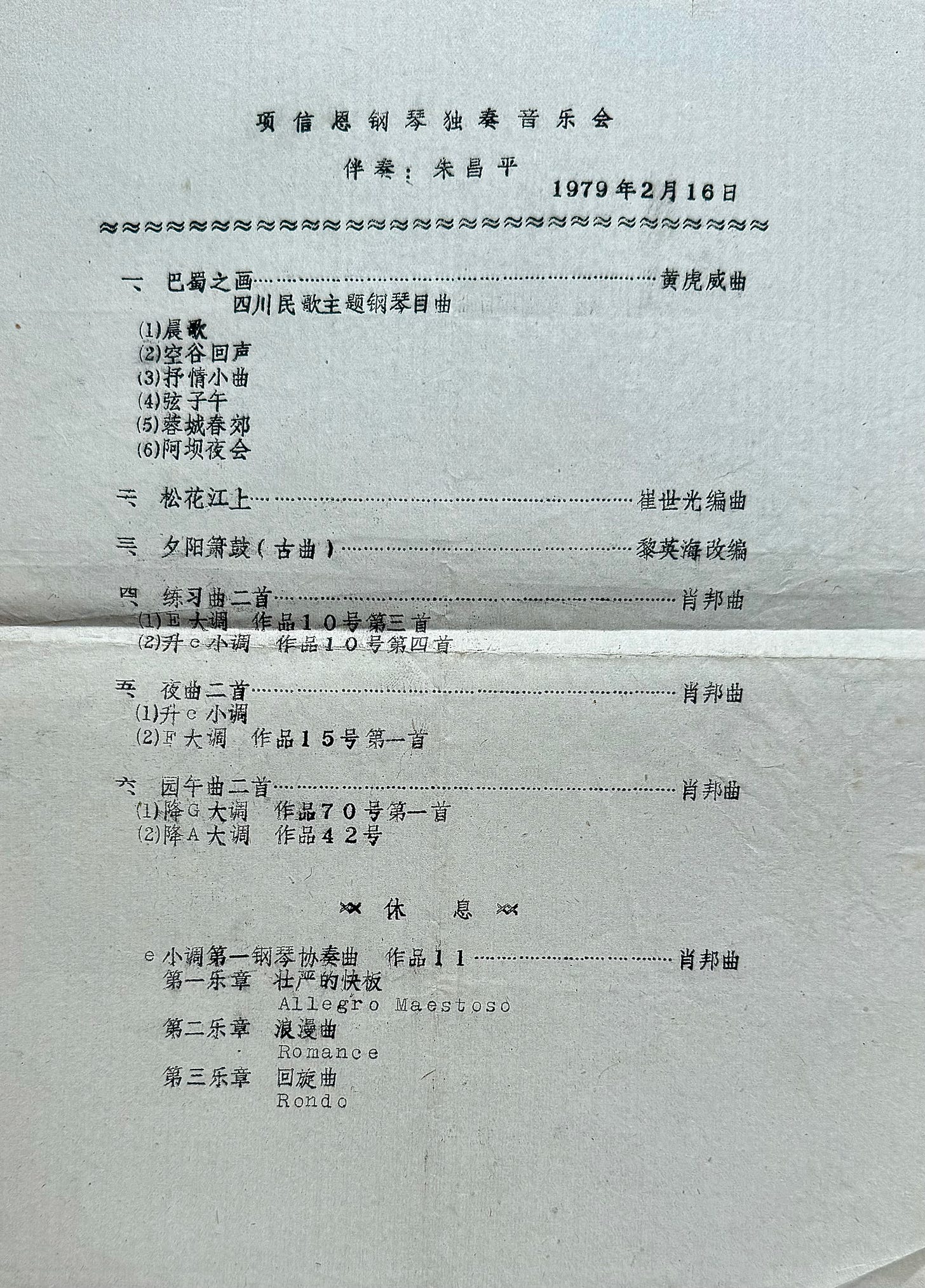

On the floor, there are several large manilla envelopes; their contents contain Mom’s six-decade-long teaching and performing career. She kept all the concert program notes, those of her own, and those of her students—they survived multiple moves across the continents and are content to be kept in these unassuming pale-yellow paper containers. Among the boxes, I find a couple of unmarked CDs. I carefully insert one of them into the player and familiar music starts flowing. It is the recording of her solo concert—the only one she gave—not long after the end of the Cultural Revolution. She was among the first few to give a solo concert at the Conservatory, where she taught for 35 years.

I am grateful that Mom found the greatest love of her life in her music. In a life riddled with adversaries and turmoil, she anchored her life in one constant, her love of music. And with that love, she returned every curveball life had thrown at her. When life gave her reasons to be disappointed, angry, or sad, she found love and solace in music. When words failed to express her emotions, she turned to the world of music where she judged no one and was judged by none.

♪ ♪ ♪

Dr. BJ Miller, a palliative medicine physician and author, once said in an interview that a full life includes sorrow and things you can’t change; and it takes a lot to learn to sit with things you can’t change in this life. I hold on to the hope that Mom’s love of music had made up for the losses she experienced and my inadequacies as a daughter who had been too often impatient and absorbed in her own life; I hope her love of music and her love of me filled in the physical distance that was between us ever since I left our home in Shanghai more than three decades ago; I hope that the absence of I love you didn’t stop her from feeling the love I had for her just as much as I felt hers.

Does unspoken love bring more pain? Does time heal the grief? I can’t help but wonder, hoping for a comforting answer. And I came upon these beautiful words from Jamie Anderson:2

Grief, I’ve learned, is really just love. It’s all the love you want to give, but cannot. All that unspent love gathers up in the corners of your eyes, the lump in your throat, and in that hollow part of your chest. Grief is just love with no place to go.

I love you, Mom! And as much as I grieve for my loss of you, I am happy that you are at a wonderful place, with God’s love and your music! ❤️

Music embedded in this essay were recordings from my mother’s Feb. 16th, 1979 solo concert at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music -

Chopin: Nocturne in F Major, Op. 15, No. 1;

黄虎威: Paintings of Sichuan (巴蜀之画) - 6 Piano pieces based on Sichuan folk songs

Chopin: Waltz in A-flat Major, Op. 42

Chopin: Nocturne in C-sharp Minor, Op. Posthume;

黎英海: Flute and Drum at Sunset

Chopin: Waltz in G-flat Major, Op. 70, No. 1

This quote is often attributed to Jamie Anderson. However, there isn't much information on this author, and it appears to be a popular internet quote without a clear source of origin. It is, nevertheless, a beautiful quote, so I am borrowing it from Jamie Anderson, whoever she/he is.

"To that shy and quiet girl, the piano was a friend she could talk to without using words, and music was a world she could escape to, a world of love and dreams." There are so many beautiful passages in this truly moving tribute to your mother, Yi. She was obviously a remarkable woman who showed her love for you in all those wonderful ways you describe. I'm sure she would have loved this wonderful tribute and I hope that writing it and sharing it helps you find your path through grief.

What a remarkable life so exquisitely captured in your tribute Yi! Lovely, lovely, lovely