Every year for the past nine years, McKinsey & Company, a leading global management consulting firm, has partnered with LeanIn.org to publish Women in the Workplace. It is the largest study of women in corporate America that offers a bird’s-eye view of the state of women in corporate America by surveying tens of thousands of employees and hundreds of employers. The report builds on the findings and data from previous years and identifies any new themes or developments.

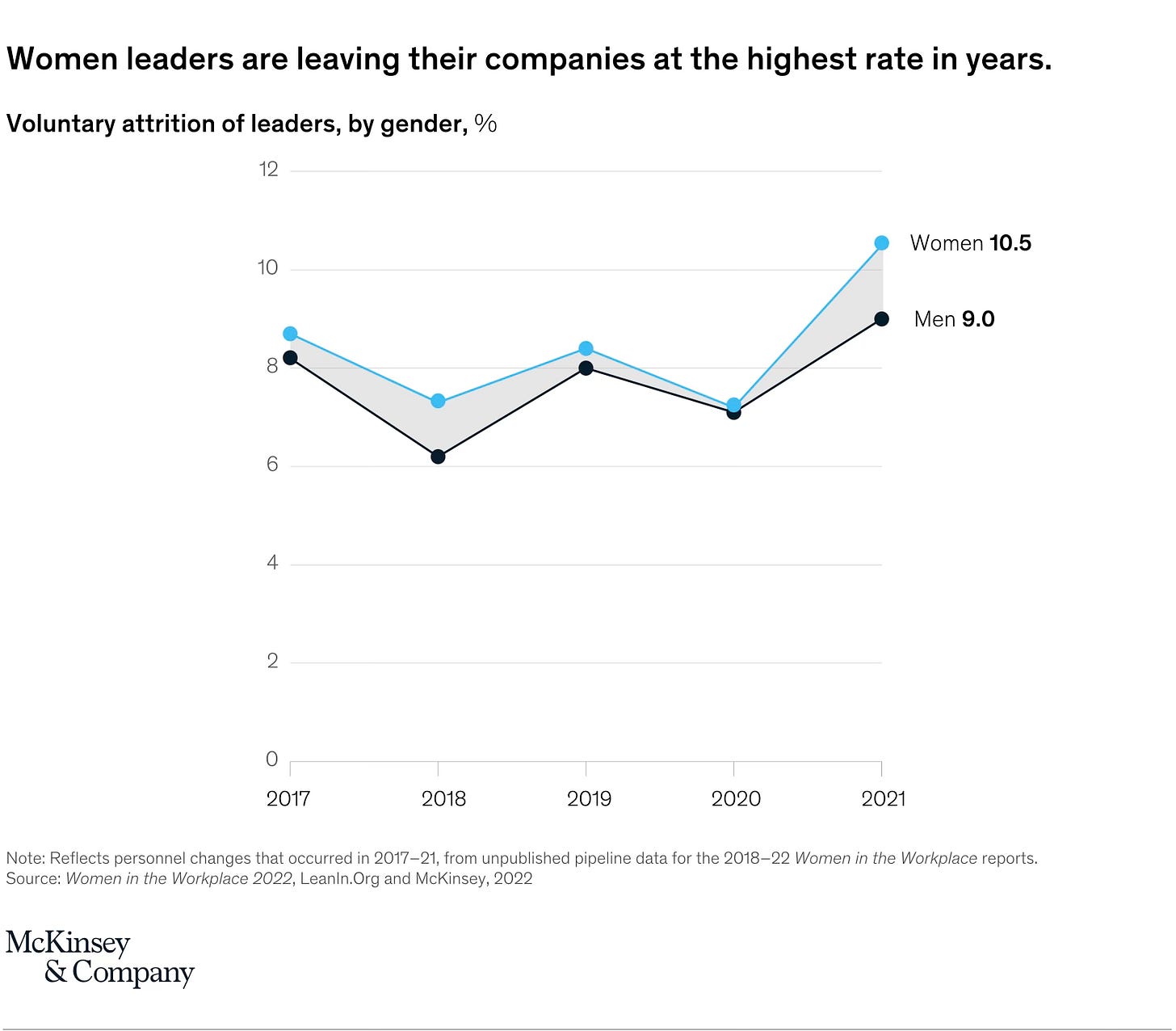

In its 2022 report, the study focused on a “Great Breakup” – women were demanding more from work and they were leaving their companies in unprecedented numbers to get it; and the existence of a “broken rung” – fewer women than men have risen through the ranks at the first step up to management. The combination of both resulted in fewer women rising through the ranks, and women leaders are leaving their companies at a much higher rate than men leaders. To put the scale of the problem in perspective: for every woman at the director level who gets promoted to the next level, two women directors are choosing to leave their company.

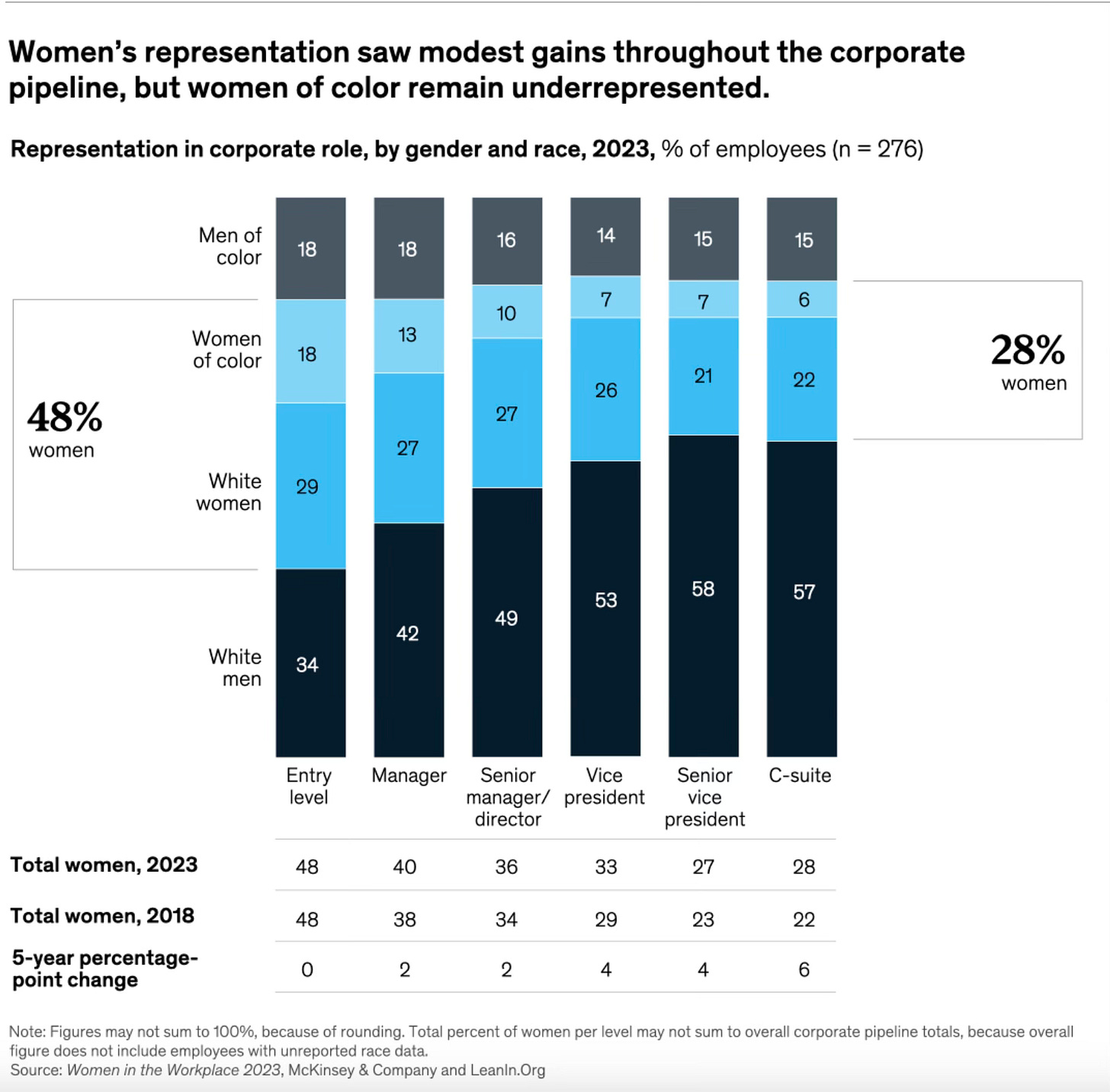

This year’s report presented the lagging progress in women leader representation in the middle-management pipeline and pointed out a consistent trend throughout the years, that underrepresentation is more pronounced for women of color in corporate America.

I did not intend to be part of statistics, but in July of last year, I joined the ranks of women leaders pulling out of the corporate world. After 25 years—22 of which were spent in a Fortune 500 company that had won the Fortune Magazine’s “Best Company to Work for” more than once—I had come to a point of realization that personal growth was not part of the reward of working hard, and meritocracy only worked up to a certain step of the ladder before encountering the glass ceiling. To an Asian American woman, there is also this phenomenon called “the bamboo ceiling”, one that is much harder to break through; and occasionally the double-edged sword of being set up as a “model minority”.

Stepping outside of the corporate “rat race” afforded me a clear mind to examine the past. It enabled me to evaluate and contemplate different types of statistics.

In my 15-plus years working in corporate management, I attended a fair number of management trainings on DEI (Diversity, Equality, and Inclusion); and joined regular company-sponsored conferences with the theme of supporting women and minorities. Such event stats would be tallied and shared at company meetings quarterly. Up-trending numbers were presented as progress made. Occasionally, I was introduced as a female leader who had “made it” and I would receive mentoring requests from young and aspiring new employees. I received mentoring sessions myself from senior women leaders on the subject of Lean In – the importance of taking a front-row seat and sitting at the table, of having an opinion and having your voice heard. Year after year, we—company executives and HR leaders as well as women leaders ourselves—got swept up in the activities, and got busy ticking the boxes. Before long, these activities began to feel like repetitive tasks on autopilot, its meaning lost in numbers and abstraction.

We grow used to evaluating progress with metrics that are “measurable” but have superficial meanings. We accept progress as being defined by “included”, but not equal. And real progress is lost in the numbers game.

I am an engineer at heart, numbers speak to me. I understand the power of numbers. But numbers don’t have meaning until we look long and hard at them to find out what they represent, and numbers don’t always represent what they are expected to represent. In the McKinsey report, women take on 48% of entry roles. That “almost equal” representation starts to change with every 100 men who are promoted from entry-level to manager positions: only 87 women are promoted, (and that number would shrink to 73 for women of color), and women are now at 40% representation level. As a result, men significantly outnumber women at the manager level, and from there on up, fewer and fewer women are promoted to the next level. When it finally comes to C-suite level, women are at 28%, and women of color, a dismal 6%.

The uneven playing field started at the manager level. We can never catch up.

After surveying more than 40,000 employees in 2022 and interviewing women of diverse identities, the McKinsey report pointed out the top 3 reasons for the “Great Breakup”: stronger headwinds than men in career advancement; feeling overworked and underrecognized; and the will to seek a different culture of work. The land starts to shift when women start to take initiative. We are no longer waiting for the company and culture to change around us. Instead, we actively seek out opportunities to join and make the changes that create rules that are fair to all. We look to define our own narratives, that diversity is as much about skin color and sex orientation as different perspectives, backgrounds, and skills; and inclusion is not just being invited but being heard and valued. When the playing field is not even, we shall refuse to play and go on to create one.

I am hopeful. To be hopeful is to know what needs to be done, and know you are not alone in having the courage to do it.

To read the other essays on The Uneven Playing Field if you missed the previous installments, you can read Part I here, Part II here, and Part III here.

Like what you read? Feel free to visit the website to read the other stories and subscribe to receive emails when new essays are posted.

The playing field was never even, but we are hopeful, the numbers of women work in higher ranking/executive positions are more than what’s in the past, and more girls studying in the STEM and management field too.

My husband called it, and I agree, it is the good old boy net work. You need to go out after work drink and party. You need to play golf how about following a football team? The socializing is what excludes women from consideration.